В този урок ще научите как да използвате Python с Redis (произнася се RED-iss, или може би REE-diss или Red-DEES, в зависимост от това кого питате), което е светкавично бързо съхраняване на ключ-стойност в паметта, което може да се използва за всичко от А до Я. Ето какво Седем бази данни за седем седмици , популярна книга за бази данни, трябва да каже за Redis:

Не е просто лесен за използване; това е радост. Ако API е UX за програмисти, тогава Redis трябва да бъде в Музея на модерното изкуство заедно с Mac Cube.

…

А що се отнася до скоростта, Redis е труден за победа. Четенията са бързи, а записите са още по-бързи, обработвайки над 100 000

SETоперации в секунда според някои показатели. (Източник)

Заинтригуван? Този урок е създаден за програмисти на Python, които може да имат нулев до малък опит с Redis. Ще се заемем с два инструмента наведнъж и ще представим както самия Redis, така и една от неговите клиентски библиотеки на Python, redis-py .

redis-py (който импортирате просто като redis ) е един от многото клиенти на Python за Redis, но има разликата, че е таксуван като „понастоящем начинът, по който трябва да се върви за Python“ от самите разработчици на Redis. Позволява ви да извиквате команди на Redis от Python и да получавате обратно познати обекти на Python.

В този урок ще разгледате :

- Инсталиране на Redis от източник и разбиране на целта на получените двоични файлове

- Изучаване на малка част от самия Redis, включително неговия синтаксис, протокол и дизайн

- Овладяване на

redis-pyкато същевременно виждате проблясъци как прилага протокола на Redis - Настройване и комуникация с сървърен екземпляр на Amazon ElastiCache Redis

Безплатно изтегляне: Вземете примерна глава от Python Tricks:Книгата, която ви показва най-добрите практики на Python с прости примери, които можете да приложите незабавно, за да пишете по-красив + Pythonic код.

Инсталиране на Redis от източник

Както е казал моят пра-пра дядо, нищо не изгражда твърдост като инсталирането от източник. Този раздел ще ви преведе през изтеглянето, създаването и инсталирането на Redis. Обещавам, че това няма да навреди!

Забележка :Този раздел е ориентиран към инсталиране на Mac OS X или Linux. Ако използвате Windows, има разклонение на Microsoft на Redis, което може да бъде инсталирано като услуга на Windows. Достатъчно е да се каже, че Redis като програма живее най-удобно на Linux кутия и че настройката и използването на Windows може да са придирчиви.

Първо, изтеглете изходния код на Redis като tarball:

$ redisurl="https://download.redis.io/redis-stable.tar.gz"

$ curl -s -o redis-stable.tar.gz $redisurl

След това превключете към root и извлечете изходния код на архива в /usr/local/lib/ :

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /usr/local/lib/

$ chmod a+w /usr/local/lib/

$ tar -C /usr/local/lib/ -xzf redis-stable.tar.gz

По желание вече можете да премахнете самия архив:

$ rm redis-stable.tar.gz

Това ще ви остави с хранилище на изходен код в /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/ . Redis е написан на C, така че ще трябва да компилирате, свържете и инсталирате с make помощна програма:

$ cd /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/

$ make && make install

Използване на make install извършва две действия:

-

Първият

makeкоманда компилира и свързва изходния код. -

make installчаст взема двоичните файлове и ги копира в/usr/local/bin/така че можете да ги стартирате отвсякъде (ако приемем, че/usr/local/bin/е вPATH).

Ето всички стъпки дотук:

$ redisurl="https://download.redis.io/redis-stable.tar.gz"

$ curl -s -o redis-stable.tar.gz $redisurl

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /usr/local/lib/

$ chmod a+w /usr/local/lib/

$ tar -C /usr/local/lib/ -xzf redis-stable.tar.gz

$ rm redis-stable.tar.gz

$ cd /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/

$ make && make install

В този момент отделете малко време, за да потвърдите, че Redis е във вашия PATH и проверете неговата версия:

$ redis-cli --version

redis-cli 5.0.3

Ако вашата обвивка не може да намери redis-cli , проверете дали /usr/local/bin/ е във вашия PATH променлива на средата и я добавете, ако не.

В допълнение към redis-cli , make install всъщност води до шепа различни изпълними файлове (и една символна връзка), които се поставят в /usr/local/bin/ :

$ # A snapshot of executables that come bundled with Redis

$ ls -hFG /usr/local/bin/redis-* | sort

/usr/local/bin/redis-benchmark*

/usr/local/bin/redis-check-aof*

/usr/local/bin/redis-check-rdb*

/usr/local/bin/redis-cli*

/usr/local/bin/redis-sentinel@

/usr/local/bin/redis-server*

Въпреки че всички те имат определена цел, двете вероятно ще ви интересуват най-много са redis-cli и redis-server , което ще очертаем скоро. Но преди да стигнем до това, трябва да настроим някаква базова конфигурация.

Конфигуриране на Redis

Redis е много конфигурируем. Въпреки че работи добре от кутията, нека отделим минута, за да зададем някои основни опции за конфигурация, които се отнасят до устойчивостта на базата данни и основната сигурност:

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /etc/redis/

$ touch /etc/redis/6379.conf

Сега напишете следното в /etc/redis/6379.conf . Ще покрием какво означават повечето от тях постепенно в целия урок:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

Конфигурацията на Redis се самодокументира с примерния redis.conf файл, намиращ се в източника на Redis за вашето удоволствие от четенето. Ако използвате Redis в производствена система, струва си да блокирате всички разсейващи фактори и да отделите време, за да прочетете този примерен файл изцяло, за да се запознаете с тънкостите на Redis и да прецизирате настройката си.

Някои уроци, включително части от документацията на Redis, може също да предложат да стартирате скрипта на Shell install_server.sh намира се в redis/utils/install_server.sh . По всякакъв начин сте добре дошли да стартирате това като по-изчерпателна алтернатива на горното, но обърнете внимание на няколко по-фини точки относно install_server.sh :

- Няма да работи на Mac OS X – само на Debian и Ubuntu Linux.

- Той ще инжектира по-пълен набор от опции за конфигурация в

/etc/redis/6379.conf. - Той ще напише System V

initскрипт към/etc/init.d/redis_6379това ще ви позволи да направитеsudo service redis_6379 start.

Ръководството за бързо стартиране на Redis също съдържа раздел за по-правилна настройка на Redis, но опциите за конфигурация по-горе трябва да са напълно достатъчни за този урок и за начало.

Забележка за сигурност: Преди няколко години авторът на Redis посочи уязвимости в сигурността в по-ранни версии на Redis, ако не е зададена конфигурация. Redis 3.2 (текущата версия 5.0.3 от март 2019 г.) направи стъпки за предотвратяване на това проникване, като зададе protected-mode опция за yes по подразбиране.

Ние изрично задаваме bind 127.0.0.1 за да позволите на Redis да слуша за връзки само от интерфейса на локалния хост, въпреки че ще трябва да разширите този бял списък в истински производствен сървър. Точката на protected-mode е като предпазна мярка, която ще имитира това поведение на свързване към локален хост, ако по друг начин не посочите нищо под bind опция.

С това на квадрат вече можем да се задълбочим в използването на самия Redis.

Десет или така минути до Redis

Този раздел ще ви предостави достатъчно познания за Redis, за да бъде опасен, като очертае неговия дизайн и основна употреба.

Първи стъпки

Redis има архитектура клиент-сървър и използва модел заявка-отговор . Това означава, че вие (клиентът) се свързвате със сървър на Redis чрез TCP връзка, на порт 6379 по подразбиране. Заявявате някакво действие (като някаква форма на четене, писане, получаване, настройка или актуализиране) и сървърът обслужва подкрепяте отговор.

Може да има много клиенти, разговарящи с един и същ сървър, което всъщност представлява Redis или всяко клиент-сървър приложение. Всеки клиент извършва (обикновено блокиращо) четене на сокет в очакване на отговора на сървъра.

cli в redis-cli означава интерфейс на командния ред и server в redis-server е за, добре, стартиране на сървър. По същия начин, по който бихте стартирали python в командния ред можете да стартирате redis-cli за да преминете към интерактивен REPL (Read Eval Print Loop), където можете да изпълнявате клиентски команди директно от обвивката.

Първо обаче ще трябва да стартирате redis-server така че да имате работещ Redis сървър, с който да говорите. Често срещан начин да направите това при разработката е да стартирате сървър на локален хост (IPv4 адрес 127.0.0.1 ), което е по подразбиране, освен ако не кажете на Redis друго. Можете също да подадете redis-server името на вашия конфигурационен файл, което е подобно на посочване на всички негови двойки ключ-стойност като аргументи на командния ред:

$ redis-server /etc/redis/6379.conf

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # oO0OoO0OoO0Oo Redis is starting oO0OoO0OoO0Oo

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # Redis version=5.0.3, bits=64, commit=00000000, modified=0, pid=31829, just started

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # Configuration loaded

Задаваме daemonize опция за конфигурация на yes , така че сървърът работи във фонов режим. (В противен случай използвайте --daemonize yes като опция за redis-server .)

Сега сте готови да стартирате Redis REPL. Въведете redis-cli на вашия команден ред. Ще видите хост:порт на сървъра двойка, последвана от > подкана:

127.0.0.1:6379>

Ето една от най-простите команди на Redis, PING , който просто тества свързаността със сървъра и връща "PONG" ако нещата са наред:

127.0.0.1:6379> PING

PONG

Командите Redis не са чувствителни към главни букви, въпреки че техните колеги от Python определено не са.

Забележка: Като друга проверка за здравина, можете да търсите идентификатора на процеса на сървъра Redis с pgrep :

$ pgrep redis-server

26983

За да убиете сървъра, използвайте pkill redis-server от командния ред. В Mac OS X можете също да използвате redis-cli shutdown .

След това ще използваме някои от често срещаните команди на Redis и ще ги сравним с това как биха изглеждали в чист Python.

Redis като речник на Python

Redis е съкращение от Услуга за отдалечен речник .

„Искаш да кажеш, като речник на Python?“ може да попитате.

да. Най-общо казано, има много паралели, които можете да направите между речник на Python (или обща хеш таблица) и това, което е и прави Redis:

-

База данни Redis съдържа ключ:стойност сдвоява и поддържа команди като

GET,SETиDEL, както и няколкостотин допълнителни команди. -

Redisключи винаги са низове.

-

Redis стойности може да са няколко различни типове данни. В този урок ще разгледаме някои от по-важните типове данни за стойности:

string,list,hashesиsets. Някои разширени типове включват геопространствени елементи и новия тип поток. -

Много команди на Redis работят в постоянно O(1) време, точно като извличане на стойност от

dictна Python или всяка хеш таблица.

Създателят на Redis Салваторе Санфилипо вероятно не би харесал сравнението на база данни на Redis с обикновен Python dict . Той нарича проекта „сървър за структура на данни“ (вместо хранилище на ключ-стойност, като memcached), тъй като Redis поддържа съхранение на допълнителни типове ключ:стойност типове данни освен string:string . Но за нашите цели тук това е полезно сравнение, ако сте запознати с обекта речник на Python.

Нека се впуснем и да се учим от пример. Първата ни база данни за играчки (с ID 0) ще бъде картографиране на country:capital city , където използваме SET за да зададете двойки ключ-стойност:

127.0.0.1:6379> SET Bahamas Nassau

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> SET Croatia Zagreb

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> GET Croatia

"Zagreb"

127.0.0.1:6379> GET Japan

(nil)

Съответната последователност от изрази в чист Python би изглеждала така:

>>>>>> capitals = {}

>>> capitals["Bahamas"] = "Nassau"

>>> capitals["Croatia"] = "Zagreb"

>>> capitals.get("Croatia")

'Zagreb'

>>> capitals.get("Japan") # None

Използваме capitals.get("Japan") вместо capitals["Japan"] защото Redis ще върне nil вместо грешка, когато ключ не е намерен, което е аналогично на None на Python .

Redis също така ви позволява да зададете и получите множество двойки ключ-стойност в една команда, MSET и MGET , съответно:

127.0.0.1:6379> MSET Lebanon Beirut Norway Oslo France Paris

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> MGET Lebanon Norway Bahamas

1) "Beirut"

2) "Oslo"

3) "Nassau"

Най-близкото нещо в Python е с dict.update() :

>>> capitals.update({

... "Lebanon": "Beirut",

... "Norway": "Oslo",

... "France": "Paris",

... })

>>> [capitals.get(k) for k in ("Lebanon", "Norway", "Bahamas")]

['Beirut', 'Oslo', 'Nassau']

Използваме .get() вместо .__getitem__() за да имитира поведението на Redis при връщане на стойност, подобна на нула, когато не е намерен ключ.

Като трети пример, EXISTS командата прави това, което звучи, а именно да провери дали съществува ключ:

127.0.0.1:6379> EXISTS Norway

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> EXISTS Sweden

(integer) 0

Python има in ключова дума за тестване на същото нещо, което насочва към dict.__contains__(key) :

>>> "Norway" in capitals

True

>>> "Sweden" in capitals

False

Тези няколко примера са предназначени да покажат, използвайки роден Python, какво се случва на високо ниво с няколко общи команди на Redis. Тук няма компонент клиент-сървър за примерите на Python и redis-py все още не е влязъл в картината. Това има за цел само да покаже функционалността на Redis чрез пример.

Ето обобщение на няколкото Redis команди, които сте виждали, и техните функционални еквиваленти на Python:

capitals["Bahamas"] = "Nassau"

capitals.get("Croatia")

capitals.update(

{

"Lebanon": "Beirut",

"Norway": "Oslo",

"France": "Paris",

}

)

[capitals[k] for k in ("Lebanon", "Norway", "Bahamas")]

"Norway" in capitals

Клиентската библиотека на Python Redis, redis-py , в който ще се потопите скоро в тази статия, прави нещата по различен начин. Той капсулира действителна TCP връзка към Redis сървър и изпраща необработени команди, като байтове, сериализирани с помощта на REdis Serialization Protocol (RESP), до сървъра. След това приема суровия отговор и го анализира обратно в обект на Python, като bytes , int или дори datetime.datetime .

Забележка :Досега разговаряхте със сървъра Redis чрез интерактивния redis-cli REPL. Можете също така да издавате команди директно, по същия начин, по който бихте предали името на скрипт на python изпълним файл, като python myscript.py .

Досега сте виждали няколко от основните типове данни на Redis, които представляват съпоставяне на string:string . Въпреки че тази двойка ключ-стойност е често срещана в повечето магазини за ключ-стойност, Redis предлага редица други възможни типове стойности, които ще видите по-нататък.

Още типове данни в Python срещу Redis

Преди да стартирате redis-py Python клиент, също така помага да имате основно разбиране за още няколко типа данни на Redis. За да бъде ясно, всички Redis ключове са низове. Това е стойността, която може да приема типове данни (или структури) в допълнение към стойностите на низове, използвани в примерите досега.

Хешит е съпоставяне на string:string , наречено поле-стойност двойки, които се намират под един ключ от най-високо ниво:

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython url "https://realpython.com/"

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython github realpython

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython fullname "Real Python"

(integer) 1

Това задава три двойки поле-стойност за единключ , "realpython" . Ако сте свикнали с терминологията и обектите на Python, това може да бъде объркващо. Хешът на Redis е приблизително аналогичен на dict на Python която е вложена едно ниво дълбоко:

data = {

"realpython": {

"url": "https://realpython.com/",

"github": "realpython",

"fullname": "Real Python",

}

}

Полетата на Redis са подобни на Python ключовете на всяка вложена двойка ключ-стойност във вътрешния речник по-горе. Redis запазва термина ключ за ключа на базата данни от най-високо ниво, който съдържа самата хеш структура.

Точно както има MSET за основния string:string двойки ключ-стойност, има и HMSET за хешове, за да зададете множество двойки вътре обекта хеш стойност:

127.0.0.1:6379> HMSET pypa url "https://www.pypa.io/" github pypa fullname "Python Packaging Authority"

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> HGETALL pypa

1) "url"

2) "https://www.pypa.io/"

3) "github"

4) "pypa"

5) "fullname"

6) "Python Packaging Authority"

Използване на HMSET вероятно е по-близък паралел за начина, по който присвоихме data към вложен речник по-горе, вместо да задава всяка вложена двойка, както се прави с HSET .

Два допълнителни типа стойности са списъци и комплекти , което може да заеме мястото на хеш или низ като стойност на Redis. Те до голяма степен са това, което звучат, така че няма да ви отнемам времето с допълнителни примери. Хешовете, списъците и наборите имат някои команди, които са специфични за дадения тип данни, които в някои случаи са обозначени с началната им буква:

-

Хешове: Командите за работа с хешове започват с

H, катоHSET,HGETилиHMSET. -

Набори: Командите за работа с набори започват с

S, катоSCARD, който получава броя на елементите при зададената стойност, съответстваща на даден ключ. -

Списъци: Командите за работа със списъци започват с

LилиR. Примерите включватLPOPиRPUSH.LилиRсе отнася до коя страна на списъка се оперира. Няколко списъчни команди също са предварени сB, което означава блокиране . Блокиращата операция не позволява на други операции да я прекъсват, докато се изпълнява. НапримерBLPOPизпълнява блокиращ ляв изскачащ прозорец върху структура на списък.

Забележка: Една забележителна характеристика на типа списък на Redis е, че това е свързан списък, а не масив. Това означава, че добавянето е O(1), докато индексирането при произволен индекс е O(N).

Ето кратък списък с команди, които са специфични за низа, хеша, списъка и набора от типове данни в Redis:

| Тип | Команди |

|---|---|

| Набори | SADD , SCARD , SDIFF , SDIFFSTORE , SINTER , SINTERSTORE , SISMEMBER , SMEMBERS , SMOVE , SPOP , SRANDMEMBER , SREM , SSCAN , SUNION , SUNIONSTORE |

| Хешове | HDEL , HEXISTS , HGET , HGETALL , HINCRBY , HINCRBYFLOAT , HKEYS , HLEN , HMGET , HMSET , HSCAN , HSET , HSETNX , HSTRLEN , HVALS |

| Списъци | BLPOP , BRPOP , BRPOPLPUSH , LINDEX , LINSERT , LLEN , LPOP , LPUSH , LPUSHX , LRANGE , LREM , LSET , LTRIM , RPOP , RPOPLPUSH , RPUSH , RPUSHX |

| Стрингове | APPEND , BITCOUNT , BITFIELD , BITOP , BITPOS , DECR , DECRBY , GET , GETBIT , GETRANGE , GETSET , INCR , INCRBY , INCRBYFLOAT , MGET , MSET , MSETNX , PSETEX , SET , SETBIT , SETEX , SETNX , SETRANGE , STRLEN |

Тази таблица не е пълна картина на Redis команди и типове. Има набор от по-усъвършенствани типове данни, като геопространствени елементи, сортирани набори и HyperLogLog. На страницата команди на Redis можете да филтрирате по група структура на данни. Има също обобщение на типовете данни и въведение в типовете данни на Redis.

Тъй като ще преминем към правене на неща в Python, вече можете да изчистите базата данни с играчки с FLUSHDB и излезте от redis-cli ОТГОВОР:

127.0.0.1:6379> FLUSHDB

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> QUIT

Това ще ви върне към подканата на вашата обвивка. Можете да напуснете redis-server работи във фонов режим, тъй като ще ви е необходим и за останалата част от урока.

Използване на redis-py :Redis в Python

Сега, след като усвоихте някои основи на Redis, време е да преминете към redis-py , Python клиентът, който ви позволява да говорите с Redis от удобен за потребителя API на Python.

Първи стъпки

redis-py е добре установена клиентска библиотека на Python, която ви позволява да говорите със сървър на Redis директно чрез извиквания на Python:

$ python -m pip install redis

След това се уверете, че вашият Redis сървър все още работи и работи във фонов режим. Можете да проверите с pgrep redis-server , и ако излезете с празни ръце, рестартирайте локален сървър с redis-server /etc/redis/6379.conf .

Сега, нека да преминем към частта, ориентирана към Python. Ето „здравей свят“ на redis-py :

1>>> import redis

2>>> r = redis.Redis()

3>>> r.mset({"Croatia": "Zagreb", "Bahamas": "Nassau"})

4True

5>>> r.get("Bahamas")

6b'Nassau'

Redis , използван в ред 2, е централният клас на пакета и работният кон, с който изпълнявате (почти) всяка команда на Redis. Връзката и повторното използване на TCP сокета се извършват за вас зад кулисите и вие извиквате команди на Redis, използвайки методи на екземпляр на класа r .

Забележете също, че типът на върнатия обект, b'Nassau' в ред 6 е bytes на Python тип, а не str . Това е bytes вместо str това е най-често срещаният тип връщане в redis-py , така че може да се наложи да извикате r.get("Bahamas").decode("utf-8") в зависимост от това какво всъщност искате да направите с върнатия байтов низ.

Кодът по-горе изглежда ли познат? Методите в почти всички случаи съвпадат с името на командата Redis, която прави същото. Тук извикахте r.mset() и r.get() , които съответстват на MSET и GET в родния API на Redis.

Това също означава, че HGETALL става r.hgetall() , PING става r.ping() , и така нататък. Има няколко изключения, но правилото важи за по-голямата част от командите.

Докато аргументите на командата Redis обикновено се превеждат в подобен сигнатур на метод, те приемат Python обекти. Например извикването на r.mset() в примера по-горе използва dict на Python като негов първи аргумент, а не поредица от байт низове.

Изградихме Redis екземпляр r без аргументи, но идва в комплект с редица параметри, ако имате нужда от тях:

# From redis/client.py

class Redis(object):

def __init__(self, host='localhost', port=6379,

db=0, password=None, socket_timeout=None,

# ...

Можете да видите, че име на хост:порт по подразбиране двойката е localhost:6379 , което е точно това, от което се нуждаем в случая на нашия локално поддържан redis-server пример.

db параметърът е номерът на базата данни. Можете да управлявате няколко бази данни в Redis наведнъж и всяка се идентифицира с цяло число. Максималният брой бази данни е 16 по подразбиране.

Когато стартирате просто redis-cli от командния ред, това ви стартира от база данни 0. Използвайте -n флаг, за да стартирате нова база данни, както в redis-cli -n 5 .

Позволени типове ключове

Едно нещо, което си струва да знаете, е, че redis-py изисква да му подадете ключове, които са bytes , str , int или float . (Той ще преобразува последните 3 от тези типа в bytes преди да ги изпратите на сървъра.)

Помислете за случай, в който искате да използвате календарни дати като ключове:

>>>>>> import datetime

>>> today = datetime.date.today()

>>> visitors = {"dan", "jon", "alex"}

>>> r.sadd(today, *visitors)

Traceback (most recent call last):

# ...

redis.exceptions.DataError: Invalid input of type: 'date'.

Convert to a byte, string or number first.

Ще трябва изрично да конвертирате date на Python обект на str , което можете да направите с .isoformat() :

>>> stoday = today.isoformat() # Python 3.7+, or use str(today)

>>> stoday

'2019-03-10'

>>> r.sadd(stoday, *visitors) # sadd: set-add

3

>>> r.smembers(stoday)

{b'dan', b'alex', b'jon'}

>>> r.scard(today.isoformat())

3

За да обобщим, самият Redis позволява само низове като ключове. redis-py е малко по-либерален в това какви типове Python ще приеме, въпреки че в крайна сметка преобразува всичко в байтове, преди да ги изпрати на Redis сървър.

Пример:PyHats.com

Време е да дадем по-пълен пример. Да се преструваме, че сме решили да стартираме доходоносен уебсайт PyHats.com, който продава безобразно скъпи шапки на всеки, който ще ги купи, и сме наели вас да създадете сайта.

Ще използвате Redis, за да обработвате част от продуктовия каталог, инвентаризацията и откриването на трафик от ботове за PyHats.com.

Това е първият ден за сайта и ние ще продаваме три шапки с ограничено издание. Всяка шапка се съхранява в хеш на Redis от двойки поле-стойност, а хешът има ключ, който е с префикс на произволно цяло число, като hat:56854717 . Използване на hat: префиксът е конвенция на Redis за създаване на нещо като пространство от имена в Redis база данни:

import random

random.seed(444)

hats = {f"hat:{random.getrandbits(32)}": i for i in (

{

"color": "black",

"price": 49.99,

"style": "fitted",

"quantity": 1000,

"npurchased": 0,

},

{

"color": "maroon",

"price": 59.99,

"style": "hipster",

"quantity": 500,

"npurchased": 0,

},

{

"color": "green",

"price": 99.99,

"style": "baseball",

"quantity": 200,

"npurchased": 0,

})

}

Нека започнем с база данни 1 тъй като използвахме база данни 0 в предишен пример:

>>> r = redis.Redis(db=1)

За да направим първоначално записване на тези данни в Redis, можем да използваме .hmset() (хеш мултинабор), извиквайки го за всеки речник. „Мулти“ е препратка към задаване на множество двойки поле-стойност, където „поле“ в този случай съответства на ключ от всеки от вложените речници в hats :

1>>> with r.pipeline() as pipe:

2... for h_id, hat in hats.items():

3... pipe.hmset(h_id, hat)

4... pipe.execute()

5Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

6Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

7Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

8[True, True, True]

9

10>>> r.bgsave()

11True

Кодовият блок по-горе също въвежда концепцията за конвейериране на Redis , което е начин да намалите броя на двупосочните транзакции, които са ви необходими за запис или четене на данни от вашия Redis сървър. Ако току-що щяхте да извикате r.hmset() три пъти, тогава това ще наложи операция за двупосочно движение напред-назад за всеки написан ред.

С конвейер всички команди се буферират от страна на клиента и след това се изпращат наведнъж, с един замах, като се използва pipe.hmset() в ред 3. Ето защо трите True всички отговори се връщат наведнъж, когато извикате pipe.execute() в ред 4. Скоро ще видите по-усъвършенстван случай на използване на конвейер.

Забележка :Документите на Redis предоставят пример за правене на същото нещо с redis-cli , където можете да предавате съдържанието на локален файл, за да извършите масово вмъкване.

Нека направим бърза проверка дали всичко е там в нашата база данни Redis:

>>>>>> pprint(r.hgetall("hat:56854717"))

{b'color': b'green',

b'npurchased': b'0',

b'price': b'99.99',

b'quantity': b'200',

b'style': b'baseball'}

>>> r.keys() # Careful on a big DB. keys() is O(N)

[b'56854717', b'1236154736', b'1326692461']

Първото нещо, което искаме да симулираме, е какво се случва, когато потребителят кликне върху Покупка . Ако артикулът е на склад, увеличете неговия npurchased с 1 и намалете неговото quantity (инвентар) с 1. Можете да използвате .hincrby() за да направите това:

>>> r.hincrby("hat:56854717", "quantity", -1)

199

>>> r.hget("hat:56854717", "quantity")

b'199'

>>> r.hincrby("hat:56854717", "npurchased", 1)

1

Забележка :HINCRBY все още работи с хеш стойност, която е низ, но се опитва да интерпретира низа като 64-битово цяло число със знак от база 10, за да изпълни операцията.

Това се отнася за други команди, свързани с увеличаване и декрементиране за други структури от данни, а именно INCR , INCRBY , INCRBYFLOAT , ZINCRBY и HINCRBYFLOAT . Ще получите грешка, ако низът със стойността не може да бъде представен като цяло число.

Но всъщност не е толкова просто. Промяна на quantity и npurchased в два реда код крие реалността, че едно щракване, покупка и плащане включват повече от това. Трябва да направим още няколко проверки, за да сме сигурни, че няма да оставим някой с по-лек портфейл и без шапка:

- Стъпка 1: Проверете дали артикулът е наличен или по друг начин подайте изключение в задната част.

- Step 2: If it is in stock, then execute the transaction, decrease the

quantityfield, and increase thenpurchasedполе. - Step 3: Be alert for any changes that alter the inventory in between the first two steps (a race condition).

Step 1 is relatively straightforward:it consists of an .hget() to check the available quantity.

Step 2 is a little bit more involved. The pair of increase and decrease operations need to be executed atomically :either both should be completed successfully, or neither should be (in the case that at least one fails).

With client-server frameworks, it’s always crucial to pay attention to atomicity and look out for what could go wrong in instances where multiple clients are trying to talk to the server at once. The answer to this in Redis is to use a transaction block, meaning that either both or neither of the commands get through.

In redis-py , Pipeline is a transactional pipeline class by default. This means that, even though the class is actually named for something else (pipelining), it can be used to create a transaction block also.

In Redis, a transaction starts with MULTI and ends with EXEC :

1127.0.0.1:6379> MULTI

2127.0.0.1:6379> HINCRBY 56854717 quantity -1

3127.0.0.1:6379> HINCRBY 56854717 npurchased 1

4127.0.0.1:6379> EXEC

MULTI (Line 1) marks the start of the transaction, and EXEC (Line 4) marks the end. Everything in between is executed as one all-or-nothing buffered sequence of commands. This means that it will be impossible to decrement quantity (Line 2) but then have the balancing npurchased increment operation fail (Line 3).

Let’s circle back to Step 3:we need to be aware of any changes that alter the inventory in between the first two steps.

Step 3 is the trickiest. Let’s say that there is one lone hat remaining in our inventory. In between the time that User A checks the quantity of hats remaining and actually processes their transaction, User B also checks the inventory and finds likewise that there is one hat listed in stock. Both users will be allowed to purchase the hat, but we have 1 hat to sell, not 2, so we’re on the hook and one user is out of their money. Not good.

Redis has a clever answer for the dilemma in Step 3:it’s called optimistic locking , and is different than how typical locking works in an RDBMS such as PostgreSQL. Optimistic locking, in a nutshell, means that the calling function (client) does not acquire a lock, but rather monitors for changes in the data it is writing to during the time it would have held a lock . If there’s a conflict during that time, the calling function simply tries the whole process again.

You can effect optimistic locking by using the WATCH command (.watch() in redis-py ), which provides a check-and-set behavior.

Let’s introduce a big chunk of code and walk through it afterwards step by step. You can picture buyitem() as being called any time a user clicks on a Buy Now or Purchase бутон. Its purpose is to confirm the item is in stock and take an action based on that result, all in a safe manner that looks out for race conditions and retries if one is detected:

1import logging

2import redis

3

4logging.basicConfig()

5

6class OutOfStockError(Exception):

7 """Raised when PyHats.com is all out of today's hottest hat"""

8

9def buyitem(r: redis.Redis, itemid: int) -> None:

10 with r.pipeline() as pipe:

11 error_count = 0

12 while True:

13 try:

14 # Get available inventory, watching for changes

15 # related to this itemid before the transaction

16 pipe.watch(itemid)

17 nleft: bytes = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

18 if nleft > b"0":

19 pipe.multi()

20 pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1)

21 pipe.hincrby(itemid, "npurchased", 1)

22 pipe.execute()

23 break

24 else:

25 # Stop watching the itemid and raise to break out

26 pipe.unwatch()

27 raise OutOfStockError(

28 f"Sorry, {itemid} is out of stock!"

29 )

30 except redis.WatchError:

31 # Log total num. of errors by this user to buy this item,

32 # then try the same process again of WATCH/HGET/MULTI/EXEC

33 error_count += 1

34 logging.warning(

35 "WatchError #%d: %s; retrying",

36 error_count, itemid

37 )

38 return None

The critical line occurs at Line 16 with pipe.watch(itemid) , which tells Redis to monitor the given itemid for any changes to its value. The program checks the inventory through the call to r.hget(itemid, "quantity") , in Line 17:

16pipe.watch(itemid)

17nleft: bytes = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

18if nleft > b"0":

19 # Item in stock. Proceed with transaction.

If the inventory gets touched during this short window between when the user checks the item stock and tries to purchase it, then Redis will return an error, and redis-py will raise a WatchError (Line 30). That is, if any of the hash pointed to by itemid changes after the .hget() call but before the subsequent .hincrby() calls in Lines 20 and 21, then we’ll re-run the whole process in another iteration of the while True loop as a result.

This is the “optimistic” part of the locking:rather than letting the client have a time-consuming total lock on the database through the getting and setting operations, we leave it up to Redis to notify the client and user only in the case that calls for a retry of the inventory check.

One key here is in understanding the difference between client-side and server-side operations:

nleft = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

This Python assignment brings the result of r.hget() client-side. Conversely, methods that you call on pipe effectively buffer all of the commands into one, and then send them to the server in a single request:

16pipe.multi()

17pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1)

18pipe.hincrby(itemid, "npurchased", 1)

19pipe.execute()

No data comes back to the client side in the middle of the transactional pipeline. You need to call .execute() (Line 19) to get the sequence of results back all at once.

Even though this block contains two commands, it consists of exactly one round-trip operation from client to server and back.

This means that the client can’t immediately use the result of pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1) , from Line 20, because methods on a Pipeline return just the pipe instance itself. We haven’t asked anything from the server at this point. While normally .hincrby() returns the resulting value, you can’t immediately reference it on the client side until the entire transaction is completed.

There’s a catch-22:this is also why you can’t put the call to .hget() into the transaction block. If you did this, then you’d be unable to know if you want to increment the npurchased field yet, since you can’t get real-time results from commands that are inserted into a transactional pipeline.

Finally, if the inventory sits at zero, then we UNWATCH the item ID and raise an OutOfStockError (Line 27), ultimately displaying that coveted Sold Out page that will make our hat buyers desperately want to buy even more of our hats at ever more outlandish prices:

24else:

25 # Stop watching the itemid and raise to break out

26 pipe.unwatch()

27 raise OutOfStockError(

28 f"Sorry, {itemid} is out of stock!"

29 )

Here’s an illustration. Keep in mind that our starting quantity is 199 for hat 56854717 since we called .hincrby() по-горе. Let’s mimic 3 purchases, which should modify the quantity and npurchased полета:

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> r.hmget("hat:56854717", "quantity", "npurchased") # Hash multi-get

[b'196', b'4']

Now, we can fast-forward through more purchases, mimicking a stream of purchases until the stock depletes to zero. Again, picture these coming from a whole bunch of different clients rather than just one Redis instance:

>>> # Buy remaining 196 hats for item 56854717 and deplete stock to 0

>>> for _ in range(196):

... buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> r.hmget("hat:56854717", "quantity", "npurchased")

[b'0', b'200']

Now, when some poor user is late to the game, they should be met with an OutOfStockError that tells our application to render an error message page on the frontend:

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 20, in buyitem

__main__.OutOfStockError: Sorry, hat:56854717 is out of stock!

Looks like it’s time to restock.

Using Key Expiry

Let’s introduce key expiry , which is another distinguishing feature in Redis. When you expire a key, that key and its corresponding value will be automatically deleted from the database after a certain number of seconds or at a certain timestamp.

In redis-py , one way that you can accomplish this is through .setex() , which lets you set a basic string:string key-value pair with an expiration:

1>>> from datetime import timedelta

2

3>>> # setex: "SET" with expiration

4>>> r.setex(

5... "runner",

6... timedelta(minutes=1),

7... value="now you see me, now you don't"

8... )

9True

You can specify the second argument as a number in seconds or a timedelta object, as in Line 6 above. I like the latter because it seems less ambiguous and more deliberate.

There are also methods (and corresponding Redis commands, of course) to get the remaining lifetime (time-to-live ) of a key that you’ve set to expire:

>>>>>> r.ttl("runner") # "Time To Live", in seconds

58

>>> r.pttl("runner") # Like ttl, but milliseconds

54368

Below, you can accelerate the window until expiration, and then watch the key expire, after which r.get() will return None and .exists() will return 0 :

>>> r.get("runner") # Not expired yet

b"now you see me, now you don't"

>>> r.expire("runner", timedelta(seconds=3)) # Set new expire window

True

>>> # Pause for a few seconds

>>> r.get("runner")

>>> r.exists("runner") # Key & value are both gone (expired)

0

The table below summarizes commands related to key-value expiration, including the ones covered above. The explanations are taken directly from redis-py method docstrings:

| Signature | Purpose |

|---|---|

r.setex(name, time, value) | Sets the value of key name to value that expires in time seconds, where time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.psetex(name, time_ms, value) | Sets the value of key name to value that expires in time_ms milliseconds, where time_ms can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.expire(name, time) | Sets an expire flag on key name for time seconds, where time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.expireat(name, when) | Sets an expire flag on key name , where when can be represented as an int indicating Unix time or a Python datetime object |

r.persist(name) | Removes an expiration on name |

r.pexpire(name, time) | Sets an expire flag on key name for time milliseconds, and time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.pexpireat(name, when) | Sets an expire flag on key name , where when can be represented as an int representing Unix time in milliseconds (Unix time * 1000) or a Python datetime object |

r.pttl(name) | Returns the number of milliseconds until the key name will expire |

r.ttl(name) | Returns the number of seconds until the key name will expire |

PyHats.com, Part 2

A few days after its debut, PyHats.com has attracted so much hype that some enterprising users are creating bots to buy hundreds of items within seconds, which you’ve decided isn’t good for the long-term health of your hat business.

Now that you’ve seen how to expire keys, let’s put it to use on the backend of PyHats.com.

We’re going to create a new Redis client that acts as a consumer (or watcher) and processes a stream of incoming IP addresses, which in turn may come from multiple HTTPS connections to the website’s server.

The watcher’s goal is to monitor a stream of IP addresses from multiple sources, keeping an eye out for a flood of requests from a single address within a suspiciously short amount of time.

Some middleware on the website server pushes all incoming IP addresses into a Redis list with .lpush() . Here’s a crude way of mimicking some incoming IPs, using a fresh Redis database:

>>> r = redis.Redis(db=5)

>>> r.lpush("ips", "51.218.112.236")

1

>>> r.lpush("ips", "90.213.45.98")

2

>>> r.lpush("ips", "115.215.230.176")

3

>>> r.lpush("ips", "51.218.112.236")

4

As you can see, .lpush() returns the length of the list after the push operation succeeds. Each call of .lpush() puts the IP at the beginning of the Redis list that is keyed by the string "ips" .

In this simplified simulation, the requests are all technically from the same client, but you can think of them as potentially coming from many different clients and all being pushed to the same database on the same Redis server.

Now, open up a new shell tab or window and launch a new Python REPL. In this shell, you’ll create a new client that serves a very different purpose than the rest, which sits in an endless while True loop and does a blocking left-pop BLPOP call on the ips list, processing each address:

1# New shell window or tab

2

3import datetime

4import ipaddress

5

6import redis

7

8# Where we put all the bad egg IP addresses

9blacklist = set()

10MAXVISITS = 15

11

12ipwatcher = redis.Redis(db=5)

13

14while True:

15 _, addr = ipwatcher.blpop("ips")

16 addr = ipaddress.ip_address(addr.decode("utf-8"))

17 now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

18 addrts = f"{addr}:{now.minute}"

19 n = ipwatcher.incrby(addrts, 1)

20 if n >= MAXVISITS:

21 print(f"Hat bot detected!: {addr}")

22 blacklist.add(addr)

23 else:

24 print(f"{now}: saw {addr}")

25 _ = ipwatcher.expire(addrts, 60)

Let’s walk through a few important concepts.

The ipwatcher acts like a consumer, sitting around and waiting for new IPs to be pushed on the "ips" Redis list. It receives them as bytes , such as b”51.218.112.236”, and makes them into a more proper address object with the ipaddress module:

15_, addr = ipwatcher.blpop("ips")

16addr = ipaddress.ip_address(addr.decode("utf-8"))

Then you form a Redis string key using the address and minute of the hour at which the ipwatcher saw the address, incrementing the corresponding count by 1 and getting the new count in the process:

17now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

18addrts = f"{addr}:{now.minute}"

19n = ipwatcher.incrby(addrts, 1)

If the address has been seen more than MAXVISITS , then it looks as if we have a PyHats.com web scraper on our hands trying to create the next tulip bubble. Alas, we have no choice but to give this user back something like a dreaded 403 status code.

We use ipwatcher.expire(addrts, 60) to expire the (address minute) combination 60 seconds from when it was last seen. This is to prevent our database from becoming clogged up with stale one-time page viewers.

If you execute this code block in a new shell, you should immediately see this output:

2019-03-11 15:10:41.489214: saw 51.218.112.236

2019-03-11 15:10:41.490298: saw 115.215.230.176

2019-03-11 15:10:41.490839: saw 90.213.45.98

2019-03-11 15:10:41.491387: saw 51.218.112.236

The output appears right away because those four IPs were sitting in the queue-like list keyed by "ips" , waiting to be pulled out by our ipwatcher . Using .blpop() (or the BLPOP command) will block until an item is available in the list, then pops it off. It behaves like Python’s Queue.get() , which also blocks until an item is available.

Besides just spitting out IP addresses, our ipwatcher has a second job. For a given minute of an hour (minute 1 through minute 60), ipwatcher will classify an IP address as a hat-bot if it sends 15 or more GET requests in that minute.

Switch back to your first shell and mimic a page scraper that blasts the site with 20 requests in a few milliseconds:

for _ in range(20):

r.lpush("ips", "104.174.118.18")

Finally, toggle back to the second shell holding ipwatcher , and you should see an output like this:

2019-03-11 15:15:43.041363: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.042027: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.042598: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.043143: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.043725: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.044244: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.044760: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.045288: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.045806: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.046318: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.046829: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.047392: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.047966: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.048479: saw 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Now, Ctrl +C out of the while True loop and you’ll see that the offending IP has been added to your blacklist:

>>> blacklist

{IPv4Address('104.174.118.18')}

Can you find the defect in this detection system? The filter checks the minute as .minute rather than the last 60 seconds (a rolling minute). Implementing a rolling check to monitor how many times a user has been seen in the last 60 seconds would be trickier. There’s a crafty solution using using Redis’ sorted sets at ClassDojo. Josiah Carlson’s Redis in Action also presents a more elaborate and general-purpose example of this section using an IP-to-location cache table.

Persistence and Snapshotting

One of the reasons that Redis is so fast in both read and write operations is that the database is held in memory (RAM) on the server. However, a Redis database can also be stored (persisted) to disk in a process called snapshotting. The point behind this is to keep a physical backup in binary format so that data can be reconstructed and put back into memory when needed, such as at server startup.

You already enabled snapshotting without knowing it when you set up basic configuration at the beginning of this tutorial with the save опция:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

The format is save <seconds> <changes> . This tells Redis to save the database to disk if both the given number of seconds and number of write operations against the database occurred. In this case, we’re telling Redis to save the database to disk every 60 seconds if at least one modifying write operation occurred in that 60-second timespan. This is a fairly aggressive setting versus the sample Redis config file, which uses these three save directives:

# Default redis/redis.conf

save 900 1

save 300 10

save 60 10000

An RDB snapshot is a full (rather than incremental) point-in-time capture of the database. (RDB refers to a Redis Database File.) We also specified the directory and file name of the resulting data file that gets written:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

This instructs Redis to save to a binary data file called dump.rdb in the current working directory of wherever redis-server was executed from:

$ file -b dump.rdb

data

You can also manually invoke a save with the Redis command BGSAVE :

127.0.0.1:6379> BGSAVE

Background saving started

The “BG” in BGSAVE indicates that the save occurs in the background. This option is available in a redis-py method as well:

>>> r.lastsave() # Redis command: LASTSAVE

datetime.datetime(2019, 3, 10, 21, 56, 50)

>>> r.bgsave()

True

>>> r.lastsave()

datetime.datetime(2019, 3, 10, 22, 4, 2)

This example introduces another new command and method, .lastsave() . In Redis, it returns the Unix timestamp of the last DB save, which Python gives back to you as a datetime обект. Above, you can see that the r.lastsave() result changes as a result of r.bgsave() .

r.lastsave() will also change if you enable automatic snapshotting with the save configuration option.

To rephrase all of this, there are two ways to enable snapshotting:

- Explicitly, through the Redis command

BGSAVEorredis-pymethod.bgsave() - Implicitly, through the

saveconfiguration option (which you can also set with.config_set()inredis-py)

RDB snapshotting is fast because the parent process uses the fork() system call to pass off the time-intensive write to disk to a child process, so that the parent process can continue on its way. This is what the background in BGSAVE refers to.

There’s also SAVE (.save() in redis-py ), but this does a synchronous (blocking) save rather than using fork() , so you shouldn’t use it without a specific reason.

Even though .bgsave() occurs in the background, it’s not without its costs. The time for fork() itself to occur can actually be substantial if the Redis database is large enough in the first place.

If this is a concern, or if you can’t afford to miss even a tiny slice of data lost due to the periodic nature of RDB snapshotting, then you should look into the append-only file (AOF) strategy that is an alternative to snapshotting. AOF copies Redis commands to disk in real time, allowing you to do a literal command-based reconstruction by replaying these commands.

Serialization Workarounds

Let’s get back to talking about Redis data structures. With its hash data structure, Redis in effect supports nesting one level deep:

127.0.0.1:6379> hset mykey field1 value1

The Python client equivalent would look like this:

r.hset("mykey", "field1", "value1")

Here, you can think of "field1": "value1" as being the key-value pair of a Python dict, {"field1": "value1"} , while mykey is the top-level key:

| Redis Command | Pure-Python Equivalent |

|---|---|

r.set("key", "value") | r = {"key": "value"} |

r.hset("key", "field", "value") | r = {"key": {"field": "value"}} |

But what if you want the value of this dictionary (the Redis hash) to contain something other than a string, such as a list or nested dictionary with strings as values?

Here’s an example using some JSON-like data to make the distinction clearer:

restaurant_484272 = {

"name": "Ravagh",

"type": "Persian",

"address": {

"street": {

"line1": "11 E 30th St",

"line2": "APT 1",

},

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"zip": 10016,

}

}

Say that we want to set a Redis hash with the key 484272 and field-value pairs corresponding to the key-value pairs from restaurant_484272 . Redis does not support this directly, because restaurant_484272 is nested:

>>> r.hmset(484272, restaurant_484272)

Traceback (most recent call last):

# ...

redis.exceptions.DataError: Invalid input of type: 'dict'.

Convert to a byte, string or number first.

You can in fact make this work with Redis. There are two different ways to mimic nested data in redis-py and Redis:

- Serialize the values into a string with something like

json.dumps() - Use a delimiter in the key strings to mimic nesting in the values

Let’s take a look at an example of each.

Option 1:Serialize the Values Into a String

You can use json.dumps() to serialize the dict into a JSON-formatted string:

>>> import json

>>> r.set(484272, json.dumps(restaurant_484272))

True

If you call .get() , the value you get back will be a bytes object, so don’t forget to deserialize it to get back the original object. json.dumps() and json.loads() are inverses of each other, for serializing and deserializing data, respectively:

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> pprint(json.loads(r.get(484272)))

{'address': {'city': 'New York',

'state': 'NY',

'street': '11 E 30th St',

'zip': 10016},

'name': 'Ravagh',

'type': 'Persian'}

This applies to any serialization protocol, with another common choice being yaml :

>>> import yaml # python -m pip install PyYAML

>>> yaml.dump(restaurant_484272)

'address: {city: New York, state: NY, street: 11 E 30th St, zip: 10016}\nname: Ravagh\ntype: Persian\n'

No matter what serialization protocol you choose to go with, the concept is the same:you’re taking an object that is unique to Python and converting it to a bytestring that is recognized and exchangeable across multiple languages.

Option 2:Use a Delimiter in Key Strings

There’s a second option that involves mimicking “nestedness” by concatenating multiple levels of keys in a Python dict . This consists of flattening the nested dictionary through recursion, so that each key is a concatenated string of keys, and the values are the deepest-nested values from the original dictionary. Consider our dictionary object restaurant_484272 :

restaurant_484272 = {

"name": "Ravagh",

"type": "Persian",

"address": {

"street": {

"line1": "11 E 30th St",

"line2": "APT 1",

},

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"zip": 10016,

}

}

We want to get it into this form:

{

"484272:name": "Ravagh",

"484272:type": "Persian",

"484272:address:street:line1": "11 E 30th St",

"484272:address:street:line2": "APT 1",

"484272:address:city": "New York",

"484272:address:state": "NY",

"484272:address:zip": "10016",

}

That’s what setflat_skeys() below does, with the added feature that it does inplace .set() operations on the Redis instance itself rather than returning a copy of the input dictionary:

1from collections.abc import MutableMapping

2

3def setflat_skeys(

4 r: redis.Redis,

5 obj: dict,

6 prefix: str,

7 delim: str = ":",

8 *,

9 _autopfix=""

10) -> None:

11 """Flatten `obj` and set resulting field-value pairs into `r`.

12

13 Calls `.set()` to write to Redis instance inplace and returns None.

14

15 `prefix` is an optional str that prefixes all keys.

16 `delim` is the delimiter that separates the joined, flattened keys.

17 `_autopfix` is used in recursive calls to created de-nested keys.

18

19 The deepest-nested keys must be str, bytes, float, or int.

20 Otherwise a TypeError is raised.

21 """

22 allowed_vtypes = (str, bytes, float, int)

23 for key, value in obj.items():

24 key = _autopfix + key

25 if isinstance(value, allowed_vtypes):

26 r.set(f"{prefix}{delim}{key}", value)

27 elif isinstance(value, MutableMapping):

28 setflat_skeys(

29 r, value, prefix, delim, _autopfix=f"{key}{delim}"

30 )

31 else:

32 raise TypeError(f"Unsupported value type: {type(value)}")

The function iterates over the key-value pairs of obj , first checking the type of the value (Line 25) to see if it looks like it should stop recursing further and set that key-value pair. Otherwise, if the value looks like a dict (Line 27), then it recurses into that mapping, adding the previously seen keys as a key prefix (Line 28).

Let’s see it at work:

>>>>>> r.flushdb() # Flush database: clear old entries

>>> setflat_skeys(r, restaurant_484272, 484272)

>>> for key in sorted(r.keys("484272*")): # Filter to this pattern

... print(f"{repr(key):35}{repr(r.get(key)):15}")

...

b'484272:address:city' b'New York'

b'484272:address:state' b'NY'

b'484272:address:street:line1' b'11 E 30th St'

b'484272:address:street:line2' b'APT 1'

b'484272:address:zip' b'10016'

b'484272:name' b'Ravagh'

b'484272:type' b'Persian'

>>> r.get("484272:address:street:line1")

b'11 E 30th St'

The final loop above uses r.keys("484272*") , where "484272*" is interpreted as a pattern and matches all keys in the database that begin with "484272" .

Notice also how setflat_skeys() calls just .set() rather than .hset() , because we’re working with plain string:string field-value pairs, and the 484272 ID key is prepended to each field string.

Encryption

Another trick to help you sleep well at night is to add symmetric encryption before sending anything to a Redis server. Consider this as an add-on to the security that you should make sure is in place by setting proper values in your Redis configuration. The example below uses the cryptography package:

$ python -m pip install cryptography

To illustrate, pretend that you have some sensitive cardholder data (CD) that you never want to have sitting around in plaintext on any server, no matter what. Before caching it in Redis, you can serialize the data and then encrypt the serialized string using Fernet:

>>>>>> import json

>>> from cryptography.fernet import Fernet

>>> cipher = Fernet(Fernet.generate_key())

>>> info = {

... "cardnum": 2211849528391929,

... "exp": [2020, 9],

... "cv2": 842,

... }

>>> r.set(

... "user:1000",

... cipher.encrypt(json.dumps(info).encode("utf-8"))

... )

>>> r.get("user:1000")

b'gAAAAABcg8-LfQw9TeFZ1eXbi' # ... [truncated]

>>> cipher.decrypt(r.get("user:1000"))

b'{"cardnum": 2211849528391929, "exp": [2020, 9], "cv2": 842}'

>>> json.loads(cipher.decrypt(r.get("user:1000")))

{'cardnum': 2211849528391929, 'exp': [2020, 9], 'cv2': 842}

Because info contains a value that is a list , you’ll need to serialize this into a string that’s acceptable by Redis. (You could use json , yaml , or any other serialization for this.) Next, you encrypt and decrypt that string using the cipher обект. You need to deserialize the decrypted bytes using json.loads() so that you can get the result back into the type of your initial input, a dict .

Забележка :Fernet uses AES 128 encryption in CBC mode. See the cryptography docs for an example of using AES 256. Whatever you choose to do, use cryptography , not pycrypto (imported as Crypto ), which is no longer actively maintained.

If security is paramount, encrypting strings before they make their way across a network connection is never a bad idea.

Compression

One last quick optimization is compression. If bandwidth is a concern or you’re cost-conscious, you can implement a lossless compression and decompression scheme when you send and receive data from Redis. Here’s an example using the bzip2 compression algorithm, which in this extreme case cuts down on the number of bytes sent across the connection by a factor of over 2,000:

>>> 1>>> import bz2

2

3>>> blob = "i have a lot to talk about" * 10000

4>>> len(blob.encode("utf-8"))

5260000

6

7>>> # Set the compressed string as value

8>>> r.set("msg:500", bz2.compress(blob.encode("utf-8")))

9>>> r.get("msg:500")

10b'BZh91AY&SY\xdaM\x1eu\x01\x11o\x91\x80@\x002l\x87\' # ... [truncated]

11>>> len(r.get("msg:500"))

12122

13>>> 260_000 / 122 # Magnitude of savings

142131.1475409836066

15

16>>> # Get and decompress the value, then confirm it's equal to the original

17>>> rblob = bz2.decompress(r.get("msg:500")).decode("utf-8")

18>>> rblob == blob

19True

The way that serialization, encryption, and compression are related here is that they all occur client-side. You do some operation on the original object on the client-side that ends up making more efficient use of Redis once you send the string over to the server. The inverse operation then happens again on the client side when you request whatever it was that you sent to the server in the first place.

Using Hiredis

It’s common for a client library such as redis-py to follow a protocol in how it is built. In this case, redis-py implements the REdis Serialization Protocol, or RESP.

Part of fulfilling this protocol consists of converting some Python object in a raw bytestring, sending it to the Redis server, and parsing the response back into an intelligible Python object.

For example, the string response “OK” would come back as "+OK\r\n" , while the integer response 1000 would come back as ":1000\r\n" . This can get more complex with other data types such as RESP arrays.

A parser is a tool in the request-response cycle that interprets this raw response and crafts it into something recognizable to the client. redis-py ships with its own parser class, PythonParser , which does the parsing in pure Python. (See .read_response() if you’re curious.)

However, there’s also a C library, Hiredis, that contains a fast parser that can offer significant speedups for some Redis commands such as LRANGE . You can think of Hiredis as an optional accelerator that it doesn’t hurt to have around in niche cases.

All that you have to do to enable redis-py to use the Hiredis parser is to install its Python bindings in the same environment as redis-py :

$ python -m pip install hiredis

What you’re actually installing here is hiredis-py , which is a Python wrapper for a portion of the hiredis C library.

The nice thing is that you don’t really need to call hiredis yourself. Just pip install it, and this will let redis-py see that it’s available and use its HiredisParser instead of PythonParser .

Internally, redis-py will attempt to import hiredis , and use a HiredisParser class to match it, but will fall back to its PythonParser instead, which may be slower in some cases:

# redis/utils.py

try:

import hiredis

HIREDIS_AVAILABLE = True

except ImportError:

HIREDIS_AVAILABLE = False

# redis/connection.py

if HIREDIS_AVAILABLE:

DefaultParser = HiredisParser

else:

DefaultParser = PythonParser

Using Enterprise Redis Applications

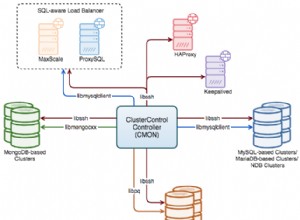

While Redis itself is open-source and free, several managed services have sprung up that offer a data store with Redis as the core and some additional features built on top of the open-source Redis server:

-

Amazon ElastiCache for Redis : This is a web service that lets you host a Redis server in the cloud, which you can connect to from an Amazon EC2 instance. For full setup instructions, you can walk through Amazon’s ElastiCache for Redis launch page.

-

Microsoft’s Azure Cache for Redis : This is another capable enterprise-grade service that lets you set up a customizable, secure Redis instance in the cloud.

The designs of the two have some commonalities. You typically specify a custom name for your cache, which is embedded as part of a DNS name, such as demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com (AWS) or demo.redis.cache.windows.net (Azure).

Once you’re set up, here are a few quick tips on how to connect.

From the command line, it’s largely the same as in our earlier examples, but you’ll need to specify a host with the h flag rather than using the default localhost. For Amazon AWS , execute the following from your instance shell:

$ export REDIS_ENDPOINT="demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com"

$ redis-cli -h $REDIS_ENDPOINT

For Microsoft Azure , you can use a similar call. Azure Cache for Redis uses SSL (port 6380) by default rather than port 6379, allowing for encrypted communication to and from Redis, which can’t be said of TCP. All that you’ll need to supply in addition is a non-default port and access key:

$ export REDIS_ENDPOINT="demo.redis.cache.windows.net"

$ redis-cli -h $REDIS_ENDPOINT -p 6380 -a <primary-access-key>

The -h flag specifies a host, which as you’ve seen is 127.0.0.1 (localhost) by default.

When you’re using redis-py in Python, it’s always a good idea to keep sensitive variables out of Python scripts themselves, and to be careful about what read and write permissions you afford those files. The Python version would look like this:

>>> import os

>>> import redis

>>> # Specify a DNS endpoint instead of the default localhost

>>> os.environ["REDIS_ENDPOINT"]

'demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com'

>>> r = redis.Redis(host=os.environ["REDIS_ENDPOINT"])

That’s all there is to it. Besides specifying a different host , you can now call command-related methods such as r.get() as normal.

Забележка :If you want to use solely the combination of redis-py and an AWS or Azure Redis instance, then you don’t really need to install and make Redis itself locally on your machine, since you don’t need either redis-cli or redis-server .

If you’re deploying a medium- to large-scale production application where Redis plays a key role, then going with AWS or Azure’s service solutions can be a scalable, cost-effective, and security-conscious way to operate.

Wrapping Up

That concludes our whirlwind tour of accessing Redis through Python, including installing and using the Redis REPL connected to a Redis server and using redis-py in real-life examples. Here’s some of what you learned:

redis-pylets you do (almost) everything that you can do with the Redis CLI through an intuitive Python API.- Mastering topics such as persistence, serialization, encryption, and compression lets you use Redis to its full potential.

- Redis transactions and pipelines are essential parts of the library in more complex situations.

- Enterprise-level Redis services can help you smoothly use Redis in production.

Redis has an extensive set of features, some of which we didn’t really get to cover here, including server-side Lua scripting, sharding, and master-slave replication. If you think that Redis is up your alley, then make sure to follow developments as it implements an updated protocol, RESP3.

Further Reading

Here are some resources that you can check out to learn more.

Books:

- Josiah Carlson: Redis in Action

- Karl Seguin: The Little Redis Book

- Luc Perkins et. al.: Seven Databases in Seven Weeks

Redis in use:

- Twitter: Real-Time Delivery Architecture at Twitter

- Spool: Redis bitmaps – Fast, easy, realtime metrics

- 3scale: Having fun with Redis Replication between Amazon and Rackspace

- Instagram: Storing hundreds of millions of simple key-value pairs in Redis

- Craigslist: Redis Sharding at Craigslist

- Disqus: Redis at Disqus

Other:

- Digital Ocean: How To Secure Your Redis Installation

- AWS: ElastiCache for Redis User Guide

- Microsoft: Azure Cache for Redis

- Cheatography: Redis Cheat Sheet

- ClassDojo: Better Rate Limiting With Redis Sorted Sets

- antirez (Salvatore Sanfilippo): Redis persistence demystified

- Martin Kleppmann: How to do distributed locking

- HighScalability: 11 Common Web Use Cases Solved in Redis